String.Split and int[] allocations

You might have already heard that it’s not always the best idea to use String.Split unless you really need all the substrings.

It might be tempting to use it when you only need the first one, or want to check how many there is but it’s totally unnecessary to allocate all these substrings if all you care about is their count.

As I found out pretty recently, it might not be the best idea to use String.Split even if you do want all the substrings.

In this post I’ll explain why that’s the case and in what scenarios it might be better to roll your own split routine.

It might be easiest to explain on an example.

Let’s say you have a string which is a set of comma-separated Guids:

var input = "{FDC4DA8B-2807-4773-9705-B68CE78D1322},{ADBE382A-C3B9-4903-85F6-12996531AAB6},{9BEB5F7F-35A8-4F8B-A9AE-A821DECE17C6},{100B7A13-038D-48C1-8ABE-F7DCCB4C6E3E},{3E520B24-0444-428E-9F68-92A8EA699EE3},{F9C51CC0-FBB2-40C8-8104-94B5D5179E62},{CA37EB0A-25FA-4B9E-9EC2-18EA2F539409},{BA3E5800-844F-4A7C-B6CF-56509868677A},{9D379F4F-0B12-469A-8721-0D6EFD345424},{75A39D08-5583-4199-B40C-8EE1534F7AEC}"

Your job is to parse them out and assign to List<Guid>.

Sounds simple and you can easily write it in just a single line of code:

var guids = input.Split(',').Select(x => new Guid(x)).ToList();

It’s clean, readable and in 99.9% of cases that’s the code you should write! In the remaining 0.1% Garbage Collector will make you question all your life choices. I was unfortunate enough to experience that myself.

You might ask: ‘What are you talking about? it’s just allocating couple strings. What’s the big deal?’ and I totally understand that skepticism. Let me try to show you what I mean by profiling this very problem using PerfView. If you’ve never heard of PerfView before and you’re writing high-performance services you should probably do some homework. There is an entire series of videos on Channel9 titled “PerfView Tutorial”. It’s from 2012, but most of it should still be relevant as the tool didn’t really change that much (at least the UI still feels like 2012).

The code I’m profiling is all in a single Main method:

public static class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

var input = "{FDC4DA8B-2807-4773-9705-B68CE78D1322},{ADBE382A-C3B9-4903-85F6-12996531AAB6},{9BEB5F7F-35A8-4F8B-A9AE-A821DECE17C6},{100B7A13-038D-48C1-8ABE-F7DCCB4C6E3E},{3E520B24-0444-428E-9F68-92A8EA699EE3},{F9C51CC0-FBB2-40C8-8104-94B5D5179E62},{CA37EB0A-25FA-4B9E-9EC2-18EA2F539409},{BA3E5800-844F-4A7C-B6CF-56509868677A},{9D379F4F-0B12-469A-8721-0D6EFD345424},{75A39D08-5583-4199-B40C-8EE1534F7AEC}";

var guids = input.Split(',').Select(x => new Guid(x)).ToList();

Console.WriteLine(guids.Count);

}

}

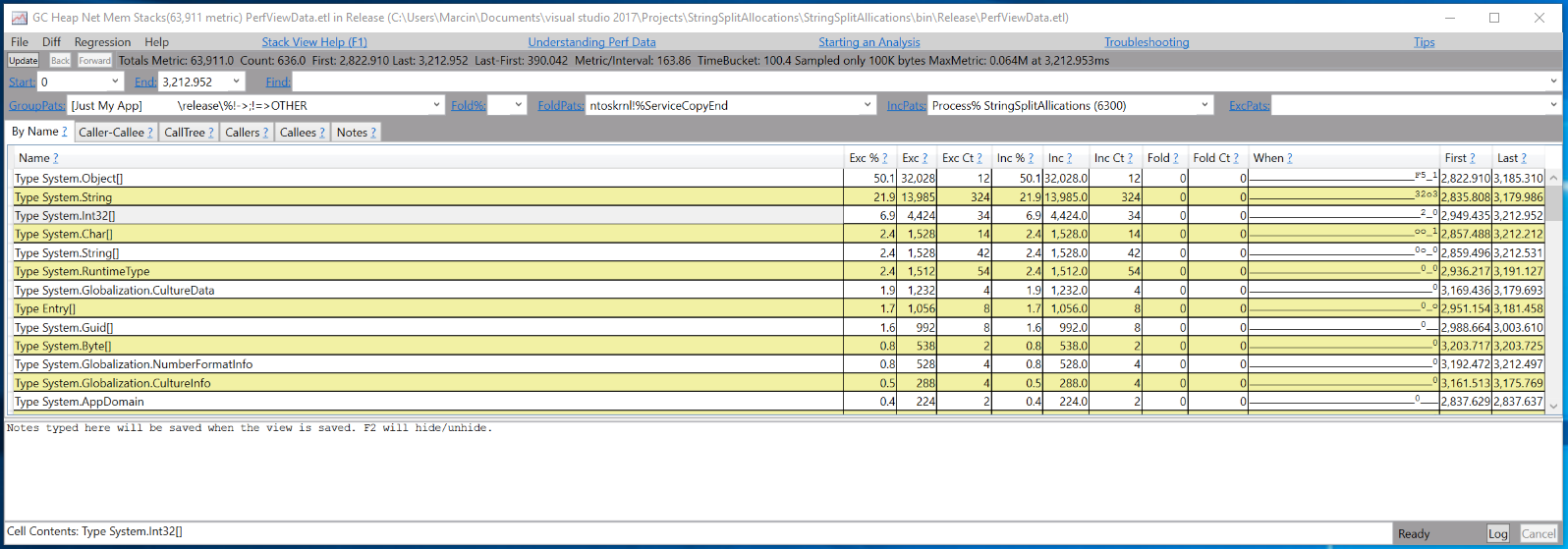

And the results will not surprise anybody:

A lot of that is stuff you’ll always see for a console application: for initial setup, Console.WriteLine, etc.

You might look at it and say it looks good.

One thing that’s easy to miss, but actually is what in certain cases might cause problems is int[] allocations.

They account for 6.9% of all allocations and if you drill down you’ll see that 4.9% from these 6.9% are coming from String.SplitInternal:

![int[] in PerfView profiling for simple solution](../../images/stringsplit/perfView-simple-intArray.png)

The first time I saw that I was quite surprised.

But when you look at how String.SplitInternal is implemented things get more clear quite quickly:

[ComVisible(false)]

internal String[] SplitInternal(char[] separator, int count, StringSplitOptions options)

{

if (count < 0)

throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException("count",

Environment.GetResourceString("ArgumentOutOfRange_NegativeCount"));

if (options < StringSplitOptions.None || options > StringSplitOptions.RemoveEmptyEntries)

throw new ArgumentException(Environment.GetResourceString("Arg_EnumIllegalVal", options));

Contract.Ensures(Contract.Result<String[]>() != null);

Contract.EndContractBlock();

bool omitEmptyEntries = (options == StringSplitOptions.RemoveEmptyEntries);

if ((count == 0) || (omitEmptyEntries && this.Length == 0))

{

return new String[0];

}

int[] sepList = new int[Length];

int numReplaces = MakeSeparatorList(separator, ref sepList);

//Handle the special case of no replaces and special count.

if (0 == numReplaces || count == 1) {

String[] stringArray = new String[1];

stringArray[0] = this;

return stringArray;

}

if(omitEmptyEntries)

{

return InternalSplitOmitEmptyEntries(sepList, null, numReplaces, count);

}

else

{

return InternalSplitKeepEmptyEntries(sepList, null, numReplaces, count);

}

}

Yes, you’re seeing correctly.

String.SplitInternal allocates int[] with the number of elements equal to the length of input string!

I bet you didn’t know about that ;)

And even though in most cases it doesn’t really matter - that int[] will be super short lived and should never leave Gen0, for very large inputs it can put non-trivial memory pressure or even push itself to LOH.

If you split large inputs and you do it a lot you should probably roll your own String.Split equivalent.

Let’s see how much more efficient that can be.

I’ll work on the same scenario we’ve already covered - parsing out a list of comma-separated Guids.

I’ve already shown you what the baseline solution is.

Here’s my take on a more efficient routine:

public List<Guid> ParseGuidsManually()

{

// allocate response list with pre-defined capacity

// walk the entire input string counting commas to get that capacity

// it's better to do that extra walk than reallocate underlying Guid[] as elements get added

int count = 0, current = 0;

while ((current = Input.IndexOf(',', current + 1)) != -1)

count++;

List<Guid> results = new List<Guid>(count);

// manually walk the input string and parsing elements out of it as they come

string substring;

int last = 0;

while ((current = Input.IndexOf(',', last)) != -1)

{

substring = Input.Substring(last, current - last);

results.Add(new Guid(substring));

last = current + 1;

}

substring = Input.Substring(last);

results.Add(new Guid(substring));

return results;

}

It does two passes through the string - first one to count all the commas and another one to actually parse the Guids out.

It’s definitely more complicated. Is it worth that extra complexity and maintenance code? The only right answer to that question is benchmark results. I’m using awesome BenchnmarkDotNet library to get my results.

Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Scaled | Gen 0 | Allocated |

--------------------------- |---------:|----------:|----------:|-------:|-------:|----------:|

ParseGuidsUsingStringSplit | 7.083 us | 0.0905 us | 0.0847 us | 1.00 | 1.4801 | 3.04 KB |

ParseGuidsManually | 6.461 us | 0.0875 us | 0.0775 us | 0.91 | 0.6638 | 1.37 KB |

OK. It’s ~10% faster and uses 45% as much memory as String.Split-based solution.

You can say it’s not worth it.

But let’s try the same benchmark with a bigger input.

Something like 10.000 guids sounds big enough to me.

[GlobalSetup]

public void Setup()

{

Input = string.Join(",", Enumerable.Range(0, 10000).Select(x => Guid.NewGuid().ToString()));

}

Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Scaled | ScaledSD | Gen 0 | Gen 1 | Gen 2 | Allocated |

--------------------------- |---------:|----------:|----------:|-------:|---------:|---------:|---------:|---------:|----------:|

ParseGuidsUsingStringSplit | 8.617 ms | 0.1797 ms | 0.2399 ms | 1.00 | 0.00 | 968.7500 | 484.3750 | 484.3750 | 2.79 MB |

ParseGuidsManually | 7.952 ms | 0.0244 ms | 0.0191 ms | 0.92 | 0.02 | 531.2500 | 125.0000 | 125.0000 | 1.3 MB |

The ratio stays similar, but the units change.

Both solutions allocate all the substrings and List<Guid> so the difference can probably be mostly attributed to that unfortunate int[] from String.Split[].

That’s 1.5MB in int[] allocated on LOH that you would never see by just looking at your code.

Can it be done even more efficiently? I bet it can, but even code like this is a huge improvement, so I won’t try to get every last CPU cycle ouf of it.

Things get even more interesting if you use String.Split in scenarios where you just shouldn’t be using it even if it wasn’t allocating int arrays.

E.g. instead of parsing Guids out lets just check how many comma separated values there are:

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)]

public int CountUsingStringSplit()

{

return Input.Split(',').Length;

}

[Benchmark]

public int CountManually()

{

int count = 0, current = 0;

while ((current = Input.IndexOf(',', current + 1)) != -1)

count++;

return count + 1;

}

Method | Mean | Error | StdDev | Scaled | Gen 0 | Gen 1 | Gen 2 | Allocated |

---------------------- |-----------:|----------:|----------:|-------:|---------:|---------:|---------:|----------:|

CountUsingStringSplit | 1,602.9 us | 18.129 us | 16.958 us | 1.00 | 431.5104 | 380.8594 | 259.5052 | 2400945 B |

CountManually | 363.7 us | 4.535 us | 4.242 us | 0.23 | - | - | - | 0 B |

It shouldn’t be surprising that manual solution is faster. But the memory usage is what it’s really about in high-performance environments like web services. Manual solution is not only over 4x faster but also does not allocate any extra memory compared to 2.4MB for the naive solution. Not allocating that extra 2.4MB means CPU can do some useful work and not clean all of that garbage as part of Garbage Collection process.

Again, I’m not saying you should never use String.Split.

It’s totally acceptable when input is small, you don’t care about every millisecond and allocating extra int[] will not make your program choke on Garbage Collection.

On the other hand, in very performance critical scenarios understanding what’s happening under the hood of String.Split can save you some headaches and make your code faster and less memory-hungry.

And an added bonus: you can always get some extra Nerd points among your coworkers, like I just did …